9 Case study: analyzing usenet text

In our final chapter, we’ll use what we’ve learned in this book to perform a start-to-finish analysis of a set of 20,000 messages sent to 20 Usenet bulletin boards in 1993. The Usenet bulletin boards in this dataset include newsgroups for topics like politics, religion, cars, sports, and cryptography, and offer a rich set of text written by many users. This data set is publicly available at http://qwone.com/~jason/20Newsgroups/ (the 20news-bydate.tar.gz file) and has become popular for exercises in text analysis and machine learning.

9.1 Pre-processing

We’ll start by reading in all the messages from the 20news-bydate folder, which are organized in sub-folders with one file for each message. We can read in files like these with a combination of read_lines(), map() and unnest().

Note that this step may take several minutes to read all the documents.

training_folder <- "data/20news-bydate/20news-bydate-train/"

# Define a function to read all files from a folder into a data frame

read_folder <- function(infolder) {

tibble(file = dir(infolder, full.names = TRUE)) %>%

mutate(text = map(file, read_lines)) %>%

transmute(id = basename(file), text) %>%

unnest(text)

}

# Use unnest() and map() to apply read_folder to each subfolder

raw_text <- tibble(folder = dir(training_folder, full.names = TRUE)) %>%

mutate(folder_out = map(folder, read_folder)) %>%

unnest(cols = c(folder_out)) %>%

transmute(newsgroup = basename(folder), id, text)

raw_text

#> # A tibble: 511,655 × 3

#> newsgroup id text

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 alt.atheism 49960 "From: mathew <mathew@mantis.co.uk>"

#> 2 alt.atheism 49960 "Subject: Alt.Atheism FAQ: Atheist Resources"

#> 3 alt.atheism 49960 "Summary: Books, addresses, music -- anything related to a…

#> 4 alt.atheism 49960 "Keywords: FAQ, atheism, books, music, fiction, addresses,…

#> 5 alt.atheism 49960 "Expires: Thu, 29 Apr 1993 11:57:19 GMT"

#> 6 alt.atheism 49960 "Distribution: world"

#> 7 alt.atheism 49960 "Organization: Mantis Consultants, Cambridge. UK."

#> 8 alt.atheism 49960 "Supersedes: <19930301143317@mantis.co.uk>"

#> 9 alt.atheism 49960 "Lines: 290"

#> 10 alt.atheism 49960 ""

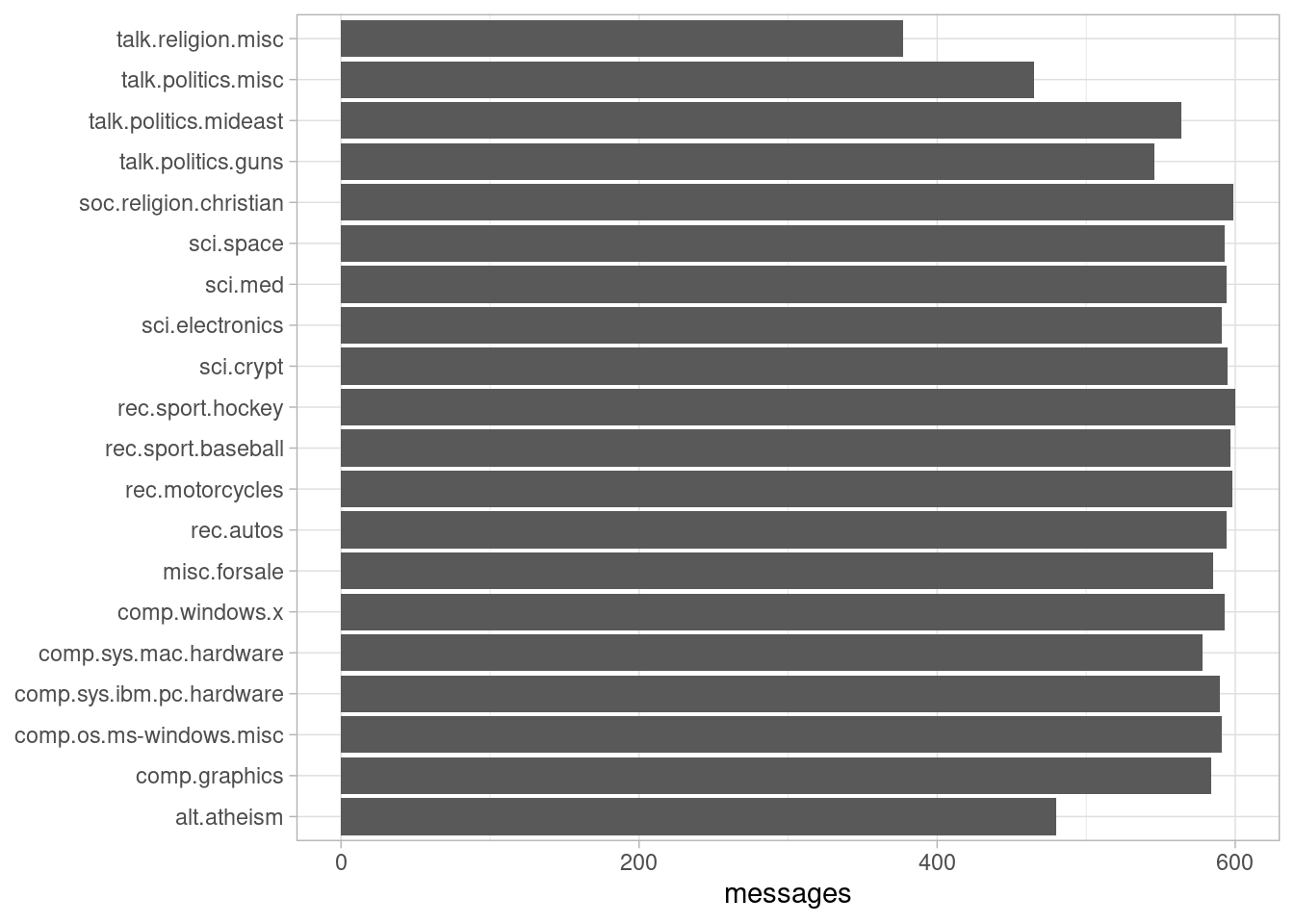

#> # ℹ 511,645 more rowsNotice the newsgroup column, which describes which of the 20 newsgroups each message comes from, and id column, which identifies a unique message within that newsgroup. What newsgroups are included, and how many messages were posted in each (Figure 9.1)?

library(ggplot2)

raw_text %>%

group_by(newsgroup) %>%

summarize(messages = n_distinct(id)) %>%

ggplot(aes(messages, newsgroup)) +

geom_col() +

labs(y = NULL)

Figure 9.1: Number of messages from each newsgroup

We can see that Usenet newsgroup names are named hierarchically, starting with a main topic such as “talk”, “sci”, or “rec”, followed by further specifications.

9.1.1 Pre-processing text

Most of the datasets we’ve examined in this book were pre-processed, meaning we didn’t have to remove, for example, copyright notices from the Jane Austen novels. Here, however, each message has some structure and extra text that we don’t want to include in our analysis. For example, every message has a header, containing field such as “from:” or “in_reply_to:” that describe the message. Some also have automated email signatures, which occur after a line like --.

This kind of pre-processing can be done within the dplyr package, using a combination of cumsum() (cumulative sum) and str_detect() from stringr.

library(stringr)

# must occur after the first occurrence of an empty line,

# and before the first occurrence of a line starting with --

cleaned_text <- raw_text %>%

group_by(newsgroup, id) %>%

filter(cumsum(text == "") > 0,

cumsum(str_detect(text, "^--")) == 0) %>%

ungroup()Many lines also have nested text representing quotes from other users, typically starting with a line like “so-and-so writes…” These can be removed with a few regular expressions.

We also choose to manually remove two messages, 9704 and

9985 that contained a large amount of non-text content.

cleaned_text <- cleaned_text %>%

filter(str_detect(text, "^[^>]+[A-Za-z\\d]") | text == "",

!str_detect(text, "writes(:|\\.\\.\\.)$"),

!str_detect(text, "^In article <"),

!id %in% c(9704, 9985))At that point, we’re ready to use unnest_tokens() to split the dataset into tokens, while removing stop-words.

library(tidytext)

usenet_words <- cleaned_text %>%

unnest_tokens(word, text) %>%

filter(str_detect(word, "[a-z']$"),

!word %in% stop_words$word)Every raw text dataset will require different steps for data cleaning, which will often involve some trial-and-error and exploration of unusual cases in the dataset. It’s important to notice that this cleaning can be achieved using tidy tools such as dplyr and tidyr.

9.2 Words in newsgroups

Now that we’ve removed the headers, signatures, and formatting, we can start exploring common words. For starters, we could find the most common words in the entire dataset, or within particular newsgroups.

usenet_words %>%

count(word, sort = TRUE)

#> # A tibble: 65,912 × 2

#> word n

#> <chr> <int>

#> 1 people 3656

#> 2 time 2709

#> 3 god 1627

#> 4 system 1610

#> 5 space 1135

#> 6 windows 1126

#> 7 program 1103

#> 8 bit 1101

#> 9 information 1094

#> 10 government 1084

#> # ℹ 65,902 more rows

words_by_newsgroup <- usenet_words %>%

count(newsgroup, word, sort = TRUE) %>%

ungroup()

words_by_newsgroup

#> # A tibble: 173,406 × 3

#> newsgroup word n

#> <chr> <chr> <int>

#> 1 soc.religion.christian god 917

#> 2 sci.space space 902

#> 3 talk.politics.mideast people 729

#> 4 sci.crypt key 704

#> 5 comp.os.ms-windows.misc windows 638

#> 6 talk.politics.mideast armenian 583

#> 7 sci.crypt db 549

#> 8 talk.politics.mideast turkish 515

#> 9 rec.autos car 512

#> 10 talk.politics.mideast armenians 509

#> # ℹ 173,396 more rows9.2.1 Finding tf-idf within newsgroups

We’d expect the newsgroups to differ in terms of topic and content, and therefore for the frequency of words to differ between them. Let’s try quantifying this using the tf-idf metric (Chapter 3).

tf_idf <- words_by_newsgroup %>%

bind_tf_idf(word, newsgroup, n) %>%

arrange(desc(tf_idf))

tf_idf

#> # A tibble: 173,406 × 6

#> newsgroup word n tf idf tf_idf

#> <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 comp.sys.ibm.pc.hardware scsi 485 0.0173 1.20 0.0209

#> 2 talk.politics.mideast armenian 583 0.00805 2.30 0.0185

#> 3 rec.motorcycles bike 324 0.0137 1.20 0.0165

#> 4 talk.politics.mideast armenians 509 0.00703 2.30 0.0162

#> 5 sci.crypt encryption 410 0.00802 1.90 0.0152

#> 6 rec.sport.hockey hockey 293 0.00815 1.61 0.0131

#> 7 rec.sport.hockey nhl 157 0.00437 3.00 0.0131

#> 8 talk.politics.misc stephanopoulos 158 0.00417 3.00 0.0125

#> 9 rec.motorcycles bikes 97 0.00410 3.00 0.0123

#> 10 comp.windows.x oname 136 0.00347 3.00 0.0104

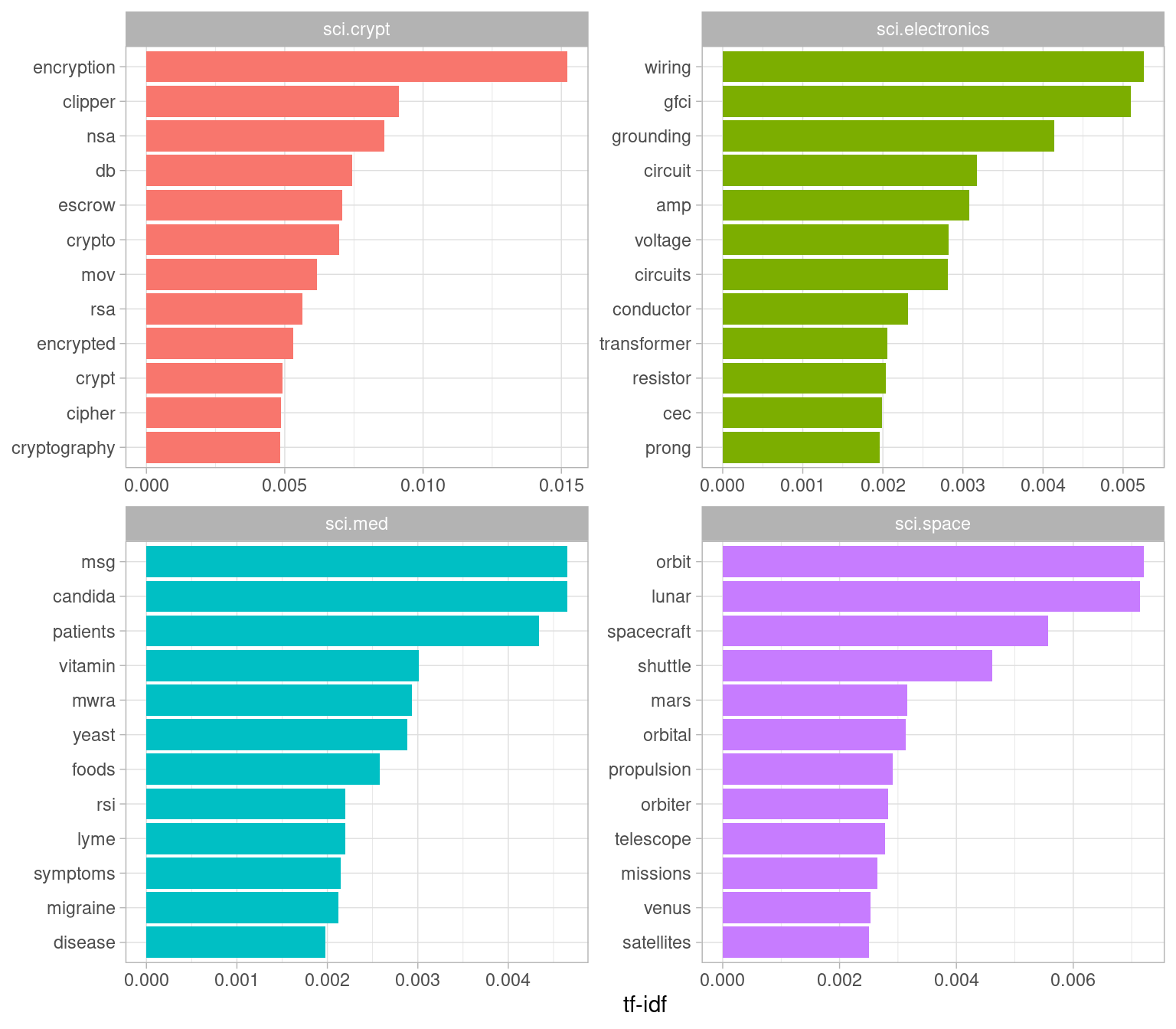

#> # ℹ 173,396 more rowsWe can examine the top tf-idf for a few selected groups to extract words specific to those topics. For example, we could look at all the sci. boards, visualized in Figure 9.2.

tf_idf %>%

filter(str_detect(newsgroup, "^sci\\.")) %>%

group_by(newsgroup) %>%

slice_max(tf_idf, n = 12) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word, tf_idf)) %>%

ggplot(aes(tf_idf, word, fill = newsgroup)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~ newsgroup, scales = "free") +

labs(x = "tf-idf", y = NULL)

Figure 9.2: Terms with the highest tf-idf within each of the science-related newsgroups

We see lots of characteristic words specific to a particular newsgroup, such as “wiring” and “circuit” on the sci.electronics topic and “orbit” and “lunar” for the space newsgroup. You could use this same code to explore other newsgroups yourself.

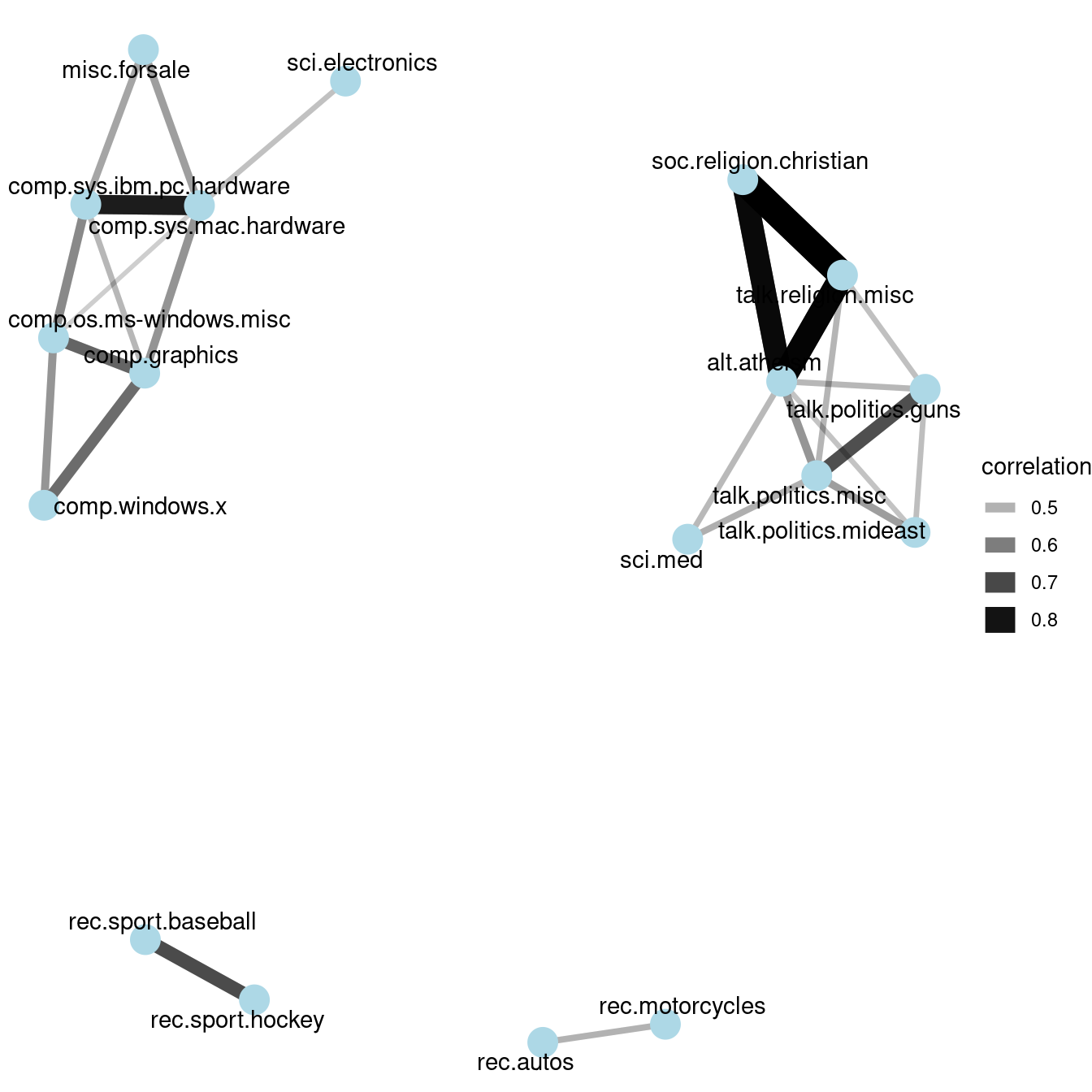

What newsgroups tended to be similar to each other in text content? We could discover this by finding the pairwise correlation of word frequencies within each newsgroup, using the pairwise_cor() function from the widyr package (see Chapter 4.2.2).

library(widyr)

newsgroup_cors <- words_by_newsgroup %>%

pairwise_cor(newsgroup, word, n, sort = TRUE)

newsgroup_cors

#> # A tibble: 380 × 3

#> item1 item2 correlation

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 talk.religion.misc soc.religion.christian 0.835

#> 2 soc.religion.christian talk.religion.misc 0.835

#> 3 alt.atheism talk.religion.misc 0.773

#> 4 talk.religion.misc alt.atheism 0.773

#> 5 alt.atheism soc.religion.christian 0.744

#> 6 soc.religion.christian alt.atheism 0.744

#> 7 comp.sys.mac.hardware comp.sys.ibm.pc.hardware 0.675

#> 8 comp.sys.ibm.pc.hardware comp.sys.mac.hardware 0.675

#> 9 rec.sport.baseball rec.sport.hockey 0.574

#> 10 rec.sport.hockey rec.sport.baseball 0.574

#> # ℹ 370 more rowsWe could then filter for stronger correlations among newsgroups, and visualize them in a network (Figure (fig:newsgroupcorsnetwork).

library(ggraph)

library(igraph)

set.seed(2017)

newsgroup_cors %>%

filter(correlation > .4) %>%

graph_from_data_frame() %>%

ggraph(layout = "fr") +

geom_edge_link(aes(alpha = correlation, width = correlation)) +

geom_node_point(size = 6, color = "lightblue") +

geom_node_text(aes(label = name), repel = TRUE) +

theme_void()

Figure 9.3: A network of Usenet groups based on the correlation of word counts between them, including only connections with a correlation greater than .4

It looks like there were four main clusters of newsgroups: computers/electronics, politics/religion, motor vehicles, and sports. This certainly makes sense in terms of what words and topics we’d expect these newsgroups to have in common.

9.2.2 Topic modeling

In Chapter 6, we used the latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) algorithm to divide a set of chapters into the books they originally came from. Could LDA do the same to sort out Usenet messages that came from different newsgroups?

Let’s try dividing up messages from the four science-related newsgroups. We first process these into a document-term matrix with cast_dtm() (Chapter 5.2), then fit the model with the LDA() function from the topicmodels package.

# include only words that occur at least 50 times

word_sci_newsgroups <- usenet_words %>%

filter(str_detect(newsgroup, "^sci")) %>%

group_by(word) %>%

mutate(word_total = n()) %>%

ungroup() %>%

filter(word_total > 50)

# convert into a document-term matrix

# with document names such as sci.crypt_14147

sci_dtm <- word_sci_newsgroups %>%

unite(document, newsgroup, id) %>%

count(document, word) %>%

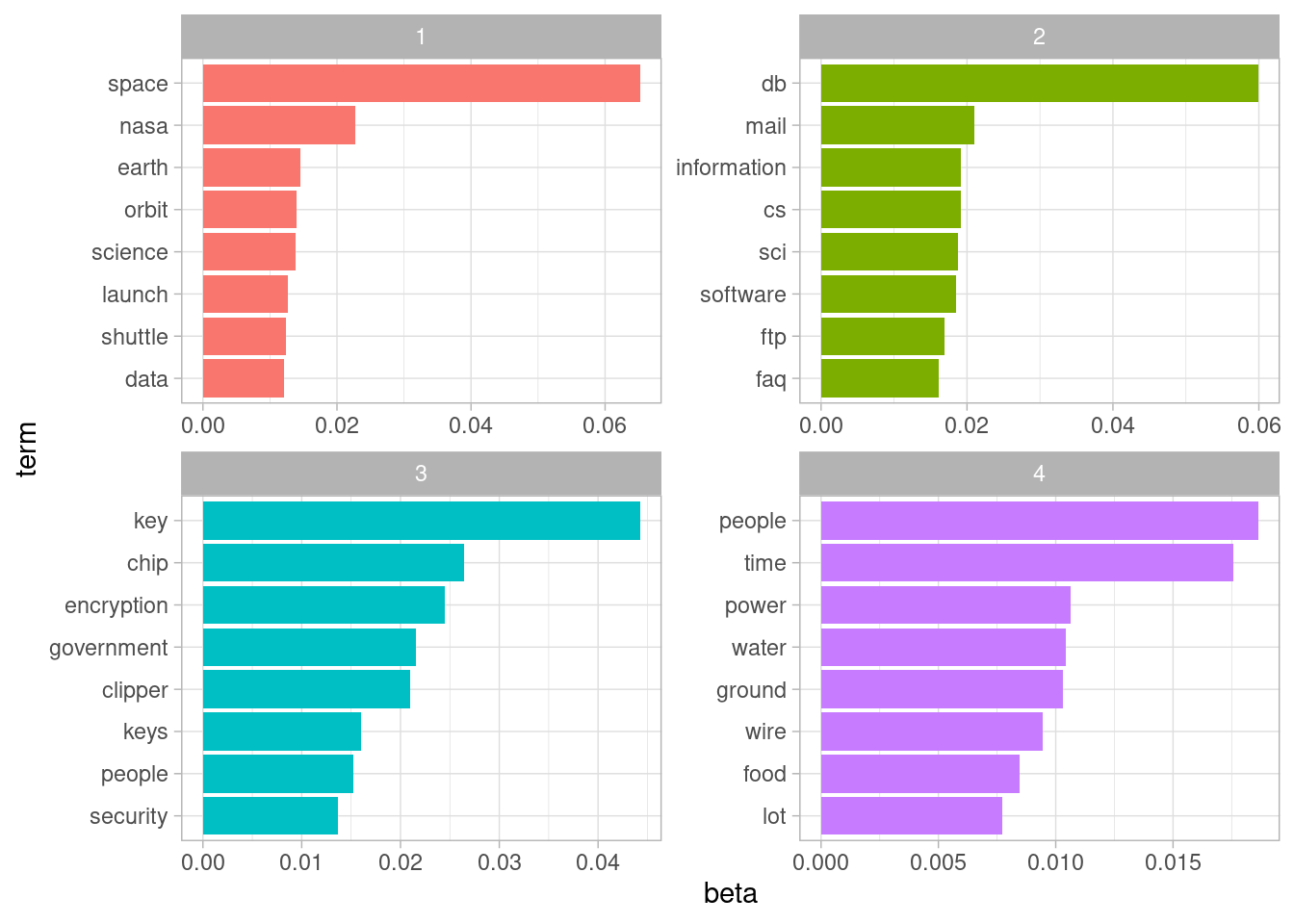

cast_dtm(document, word, n)What four topics did this model extract, and did they match the four newsgroups? This approach will look familiar from Chapter 6: we visualize each topic based on the most frequent terms within it (Figure 9.4).

sci_lda %>%

tidy() %>%

group_by(topic) %>%

slice_max(beta, n = 8) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(term = reorder_within(term, beta, topic)) %>%

ggplot(aes(beta, term, fill = factor(topic))) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~ topic, scales = "free") +

scale_y_reordered()

Figure 9.4: Top words from each topic fit by LDA on the science-related newsgroups

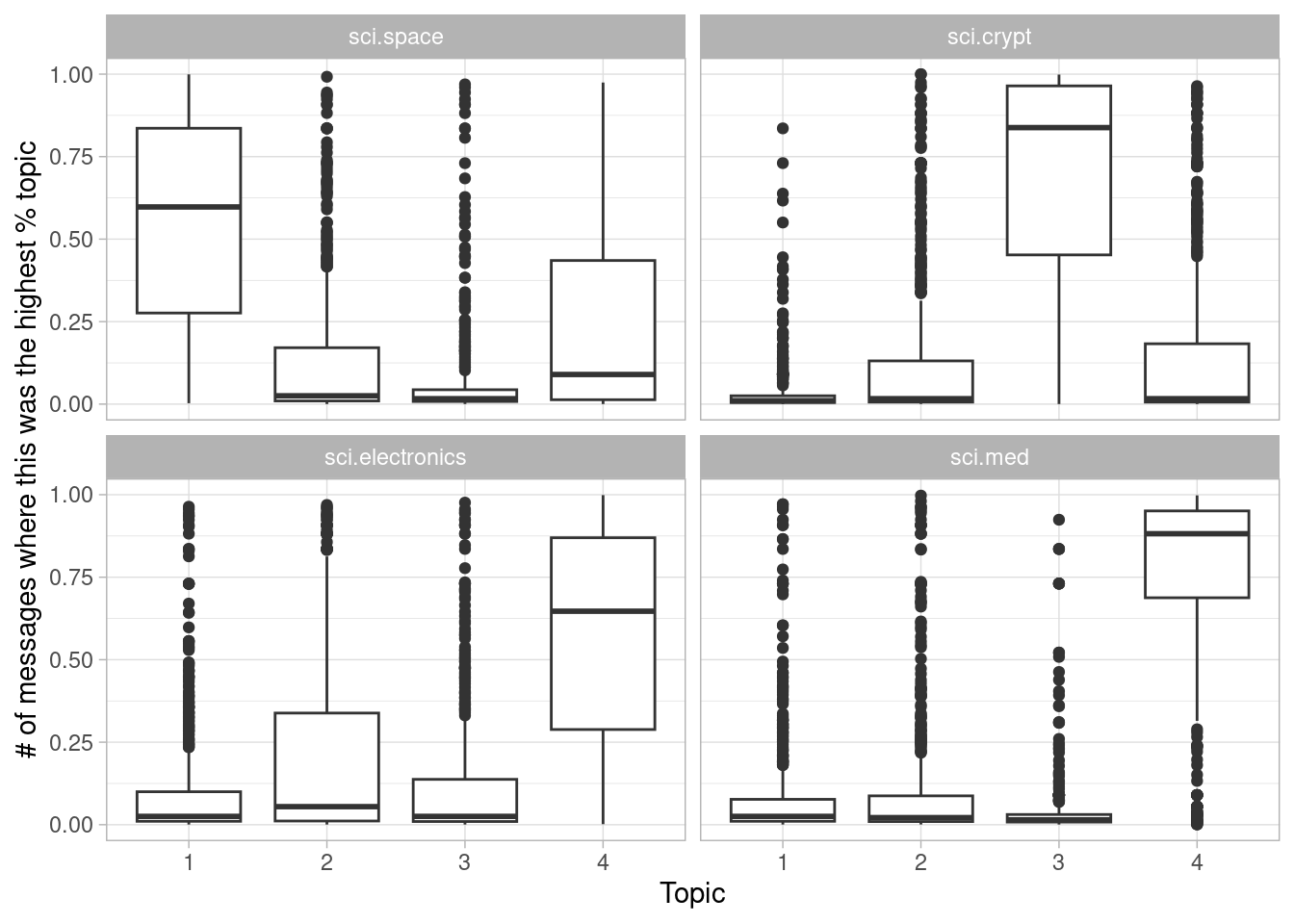

From the top words, we can start to suspect which topics may capture which newsgroups. Topic 1 certainly represents the sci.space newsgroup (thus the most common word being “space”), and topic 2 is likely drawn from cryptography, with terms such as “key” and “encryption”. Just as we did in Chapter 6.2.2, we can confirm this by seeing how documents from each newsgroup have higher “gamma” for each topic (Figure 9.5).

sci_lda %>%

tidy(matrix = "gamma") %>%

separate(document, c("newsgroup", "id"), sep = "_") %>%

mutate(newsgroup = reorder(newsgroup, gamma * topic)) %>%

ggplot(aes(factor(topic), gamma)) +

geom_boxplot() +

facet_wrap(~ newsgroup) +

labs(x = "Topic",

y = "# of messages where this was the highest % topic")

Figure 9.5: Distribution of gamma for each topic within each Usenet newsgroup

Much as we saw in the literature analysis, topic modeling was able to discover the distinct topics present in the text without needing to consult the labels.

Notice that the division of Usenet messages wasn’t as clean as the division of book chapters, with a substantial number of messages from each newsgroup getting high values of “gamma” for other topics. This isn’t surprising since many of the messages are short and could overlap in terms of common words (for example, discussions of space travel could include many of the same words as discussions of electronics). This is a realistic example of how LDA might divide documents into rough topics while still allowing a degree of overlap.

9.3 Sentiment analysis

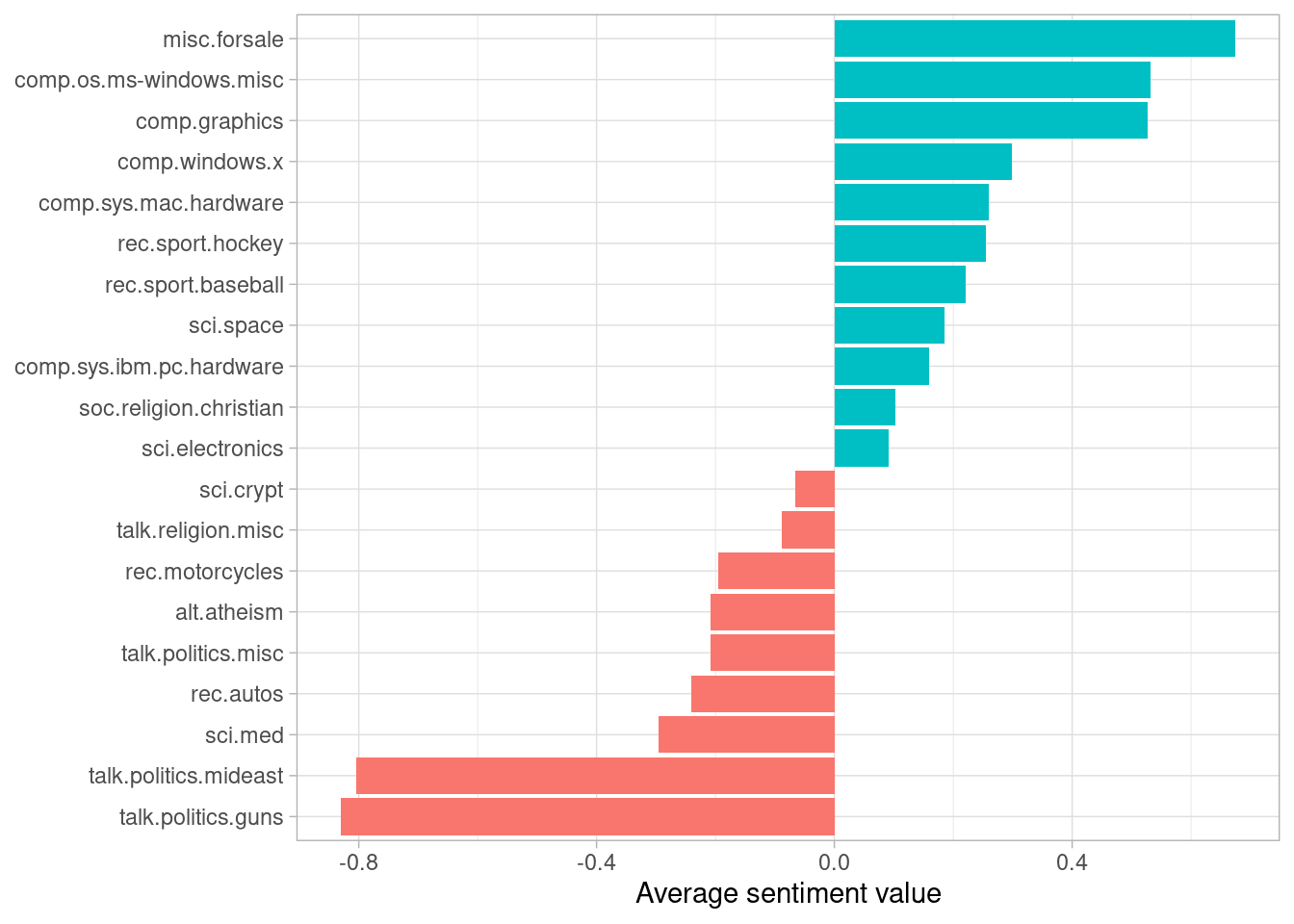

We can use the sentiment analysis techniques we explored in Chapter 2 to examine how often positive and negative words occurred in these Usenet posts. Which newsgroups were the most positive or negative overall?

In this example we’ll use the AFINN sentiment lexicon, which provides numeric positivity values for each word, and visualize it with a bar plot (Figure 9.6).

newsgroup_sentiments <- words_by_newsgroup %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("afinn"), by = "word") %>%

group_by(newsgroup) %>%

summarize(value = sum(value * n) / sum(n))

newsgroup_sentiments %>%

mutate(newsgroup = reorder(newsgroup, value)) %>%

ggplot(aes(value, newsgroup, fill = value > 0)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

labs(x = "Average sentiment value", y = NULL)

Figure 9.6: Average AFINN value for posts within each newsgroup

According to this analysis, the “misc.forsale” newsgroup was the most positive. This makes sense, since it likely included many positive adjectives about the products that users wanted to sell!

9.3.1 Sentiment analysis by word

It’s worth looking deeper to understand why some newsgroups ended up more positive or negative than others. For that, we can examine the total positive and negative contributions of each word.

contributions <- usenet_words %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("afinn"), by = "word") %>%

group_by(word) %>%

summarize(occurences = n(),

contribution = sum(value))What are these contributions?

contributions

#> # A tibble: 1,909 × 3

#> word occurences contribution

#> <chr> <int> <dbl>

#> 1 abandon 13 -26

#> 2 abandoned 19 -38

#> 3 abandons 3 -6

#> 4 abduction 2 -4

#> 5 abhor 4 -12

#> 6 abhorred 1 -3

#> 7 abhorrent 2 -6

#> 8 abilities 16 32

#> 9 ability 177 354

#> 10 aboard 8 8

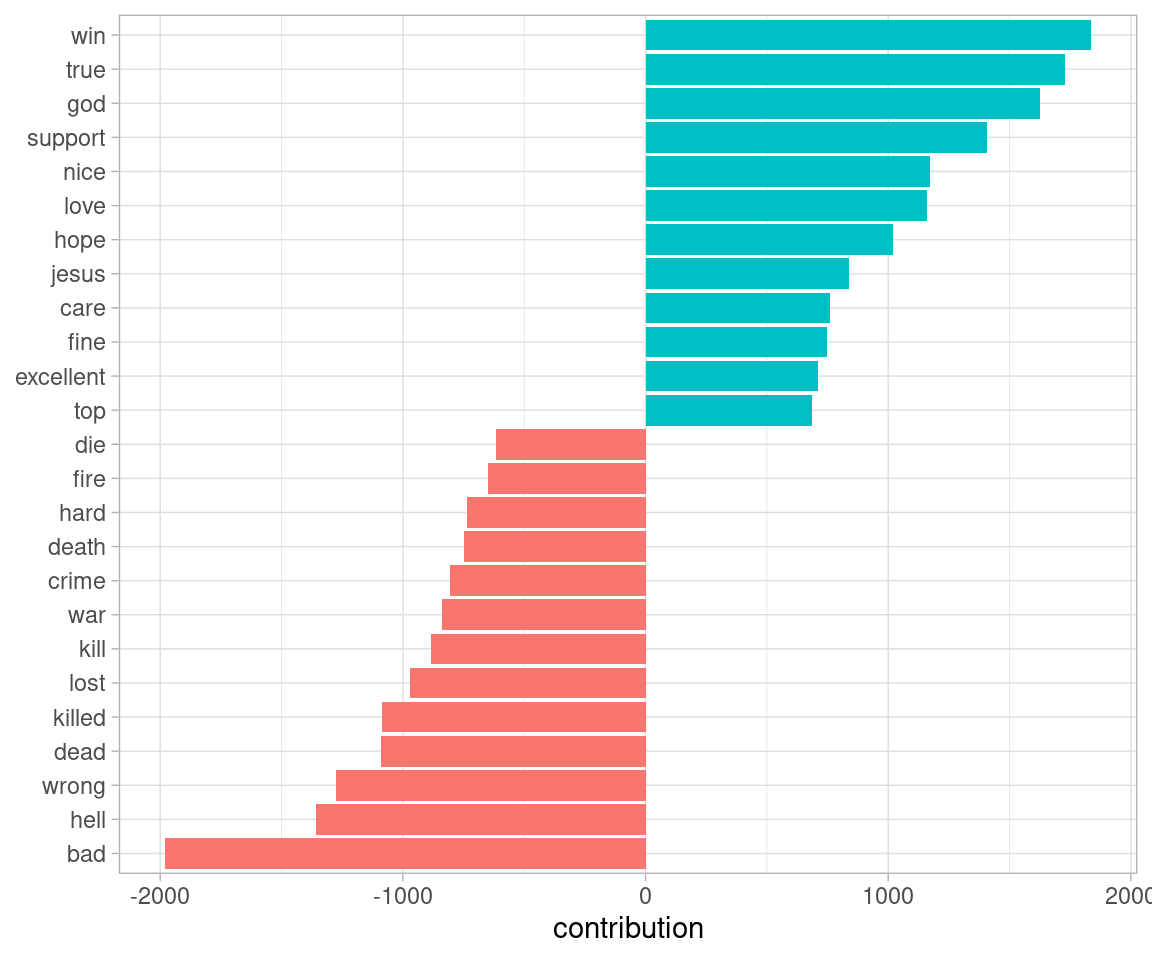

#> # ℹ 1,899 more rowsWhich words had the most effect on sentiment values overall (Figure 9.7)?

contributions %>%

slice_max(abs(contribution), n = 25) %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word, contribution)) %>%

ggplot(aes(contribution, word, fill = contribution > 0)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

labs(y = NULL)

Figure 9.7: Words with the greatest contributions to positive/negative sentiment values in the Usenet text

These words look generally reasonable as indicators of each message’s sentiment, but we can spot possible problems with the approach. “True” could just as easily be a part of “not true” or a similar negative expression, and the words “God” and “Jesus” are apparently very common on Usenet but could easily be used in many contexts, positive or negative.

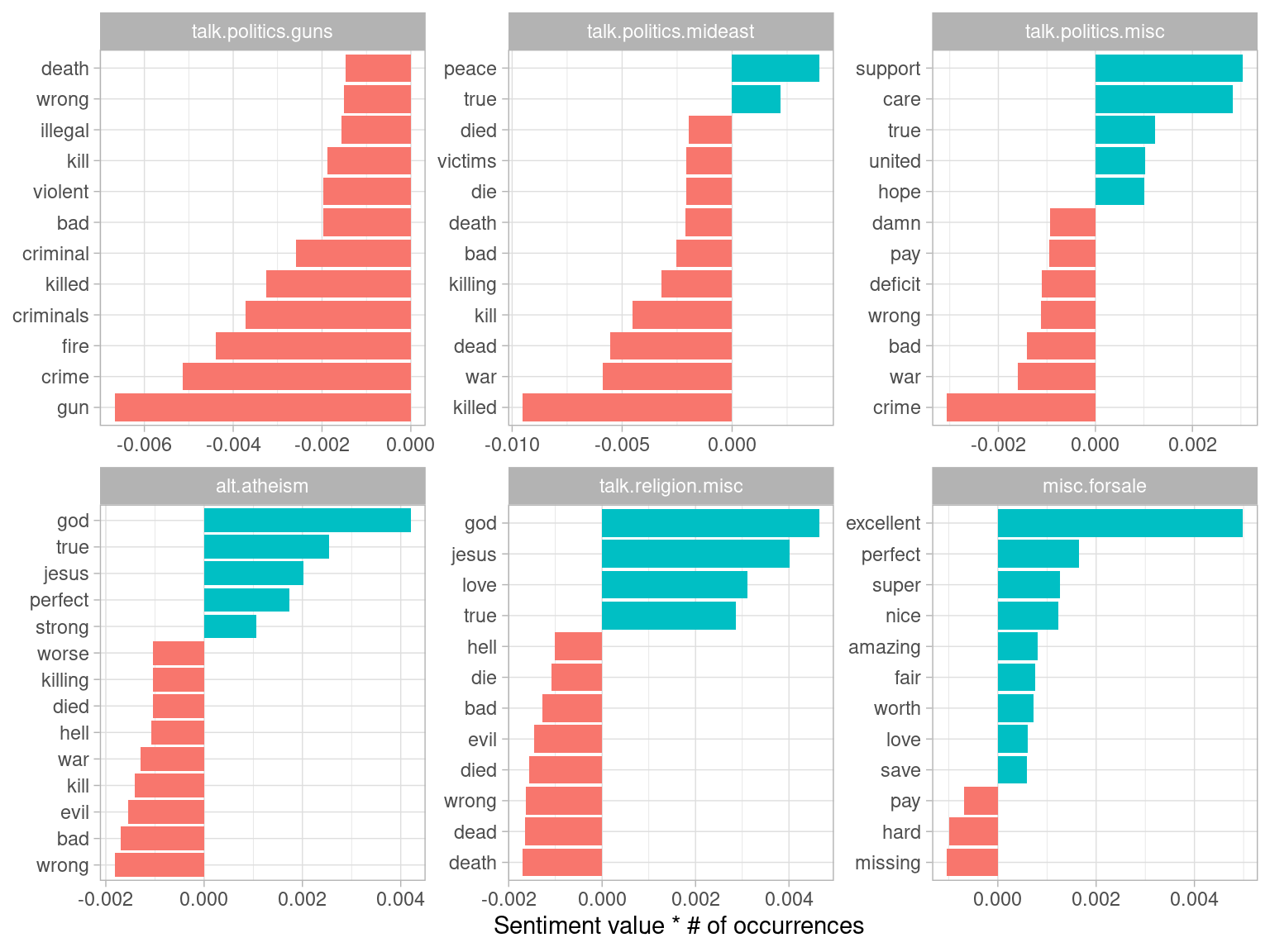

We may also care about which words contributed the most within each newsgroup, so that we can see which newsgroups might be incorrectly estimated.

top_sentiment_words <- words_by_newsgroup %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("afinn"), by = "word") %>%

mutate(contribution = value * n / sum(n))We can calculate each word’s contribution to each newsgroup’s sentiment score, and visualize the strongest contributors from a selection of the groups (Figure 9.8).

top_sentiment_words

#> # A tibble: 13,078 × 5

#> newsgroup word n value contribution

#> <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 soc.religion.christian god 917 1 0.0144

#> 2 soc.religion.christian jesus 440 1 0.00690

#> 3 talk.politics.guns gun 425 -1 -0.00667

#> 4 talk.religion.misc god 296 1 0.00464

#> 5 alt.atheism god 268 1 0.00421

#> 6 soc.religion.christian faith 257 1 0.00403

#> 7 talk.religion.misc jesus 256 1 0.00402

#> 8 talk.politics.mideast killed 202 -3 -0.00951

#> 9 talk.politics.mideast war 187 -2 -0.00587

#> 10 soc.religion.christian true 179 2 0.00562

#> # ℹ 13,068 more rows

Figure 9.8: Words that contributed the most to sentiment scores within each of six newsgroups

This confirms our hypothesis about the “misc.forsale” newsgroup: most of the sentiment was driven by positive adjectives such as “excellent” and “perfect”. We can also see how much sentiment is confounded with topic. An atheism newsgroup is likely to discuss “god” in detail even in a negative context, and we can see that it makes the newsgroup look more positive. Similarly, the negative contribution of the word “gun” to the “talk.politics.guns” group will occur even when the members are discussing guns positively.

This helps remind us that sentiment analysis can be confounded by topic, and that we should always examine the influential words before interpreting it too deeply.

9.3.2 Sentiment analysis by message

We can also try finding the most positive and negative individual messages, by grouping and summarizing by id rather than newsgroup.

sentiment_messages <- usenet_words %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("afinn"), by = "word") %>%

group_by(newsgroup, id) %>%

summarize(sentiment = mean(value),

words = n()) %>%

ungroup() %>%

filter(words >= 5)As a simple measure to reduce the role of randomness, we filtered out messages that had fewer than five words that contributed to sentiment.

What were the most positive messages?

sentiment_messages %>%

arrange(desc(sentiment))

#> # A tibble: 3,564 × 4

#> newsgroup id sentiment words

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 rec.sport.hockey 53560 3.89 18

#> 2 rec.sport.hockey 53602 3.83 30

#> 3 rec.sport.hockey 53822 3.83 6

#> 4 comp.windows.x 66905 3.32 19

#> 5 comp.windows.x 66906 3.32 19

#> 6 comp.os.ms-windows.misc 9904 3.29 7

#> 7 rec.sport.hockey 53645 3.23 13

#> 8 rec.autos 102768 3.2 5

#> 9 misc.forsale 75965 3 5

#> 10 misc.forsale 76037 3 5

#> # ℹ 3,554 more rowsLet’s check this by looking at the most positive message in the whole dataset. To assist in this we could write a short function for printing a specified message.

print_message <- function(group, message_id) {

result <- cleaned_text %>%

filter(newsgroup == group, id == message_id, text != "")

cat(result$text, sep = "\n")

}

print_message("rec.sport.hockey", 53560)

#> Everybody. Please send me your predictions for the Stanley Cup Playoffs!

#> I want to see who people think will win.!!!!!!!

#> Please Send them in this format, or something comparable:

#> 1. Winner of Buffalo-Boston

#> 2. Winner of Montreal-Quebec

#> 3. Winner of Pittsburgh-New York

#> 4. Winner of New Jersey-Washington

#> 5. Winner of Chicago-(Minnesota/St.Louis)

#> 6. Winner of Toronto-Detroit

#> 7. Winner of Vancouver-Winnipeg

#> 8. Winner of Calgary-Los Angeles

#> 9. Winner of Adams Division (1-2 above)

#> 10. Winner of Patrick Division (3-4 above)

#> 11. Winner of Norris Division (5-6 above)

#> 12. Winner of Smythe Division (7-8 above)

#> 13. Winner of Wales Conference (9-10 above)

#> 14. Winner of Campbell Conference (11-12 above)

#> 15. Winner of Stanley Cup (13-14 above)

#> I will summarize the predictions, and see who is the biggest

#> INTERNET GURU PREDICTING GUY/GAL.

#> Send entries to Richard Madison

#> rrmadiso@napier.uwaterloo.ca

#> PS: I will send my entries to one of you folks so you know when I say

#> I won, that I won!!!!!It looks like this message was chosen because it uses the word “winner” many times. How about the most negative message? Turns out it’s also from the hockey site, but has a very different attitude.

sentiment_messages %>%

arrange(sentiment)

#> # A tibble: 3,564 × 4

#> newsgroup id sentiment words

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 rec.sport.hockey 53907 -3 6

#> 2 sci.electronics 53899 -3 5

#> 3 talk.politics.mideast 75918 -3 7

#> 4 rec.autos 101627 -2.83 6

#> 5 comp.graphics 37948 -2.8 5

#> 6 comp.windows.x 67204 -2.7 10

#> 7 talk.politics.guns 53362 -2.67 6

#> 8 alt.atheism 51309 -2.6 5

#> 9 comp.sys.mac.hardware 51513 -2.6 5

#> 10 rec.autos 102883 -2.6 5

#> # ℹ 3,554 more rows

print_message("rec.sport.hockey", 53907)

#> Losers like us? You are the fucking moron who has never heard of the Western

#> Business School, or the University of Western Ontario for that matter. Why

#> don't you pull your head out of your asshole and smell something other than

#> shit for once so you can look on a map to see where UWO is! Back to hockey,

#> the North Stars should be moved because for the past few years they have

#> just been SHIT. A real team like Toronto would never be moved!!!

#> Andrew--Well, we can confidently say that the sentiment analysis worked!

9.3.3 N-gram analysis

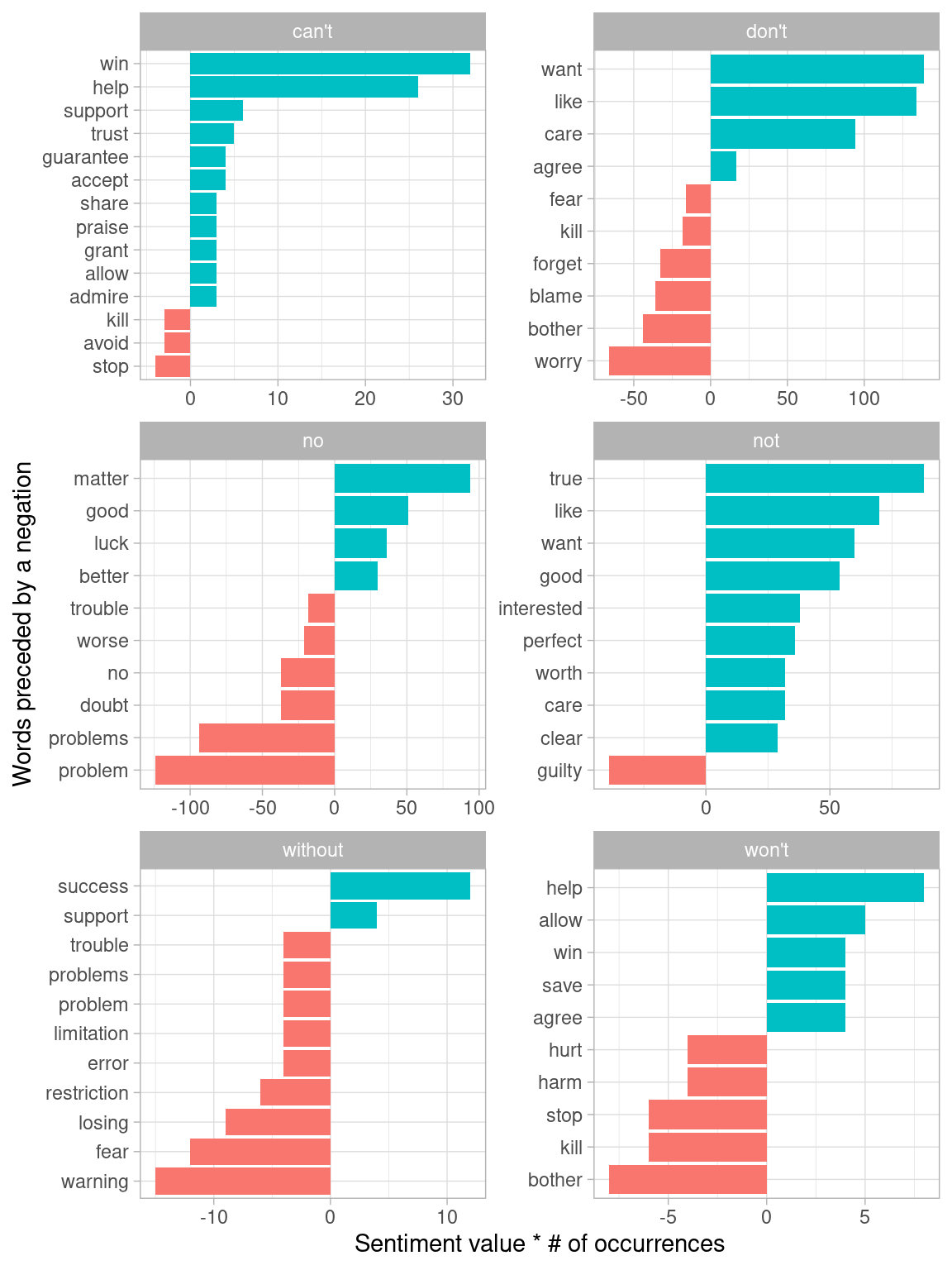

In Chapter 4, we considered the effect of words such as “not” and “no” on sentiment analysis of Jane Austen novels, such as considering whether a phrase like “don’t like” led to passages incorrectly being labeled as positive. The Usenet dataset is a much larger corpus of more modern text, so we may be interested in how sentiment analysis may be reversed in this text.

We’d start by finding and counting all the bigrams in the Usenet posts.

usenet_bigrams <- cleaned_text %>%

unnest_tokens(bigram, text, token = "ngrams", n = 2)

usenet_bigram_counts <- usenet_bigrams %>%

count(newsgroup, bigram, sort = TRUE) %>%

separate(bigram, c("word1", "word2"), sep = " ")We could then define a list of six words that we suspect are used in negation, such as “no”, “not”, and “without”, and visualize the sentiment-associated words that most often followed them (Figure 9.9). This shows the words that most often contributed in the “wrong” direction.

negate_words <- c("not", "without", "no", "can't", "don't", "won't")

usenet_bigram_counts %>%

filter(word1 %in% negate_words) %>%

count(word1, word2, wt = n, sort = TRUE) %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("afinn"), by = c(word2 = "word")) %>%

mutate(contribution = value * n) %>%

group_by(word1) %>%

slice_max(abs(contribution), n = 10) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word2 = reorder_within(word2, contribution, word1)) %>%

ggplot(aes(contribution, word2, fill = contribution > 0)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~ word1, scales = "free", nrow = 3) +

scale_y_reordered() +

labs(x = "Sentiment value * # of occurrences",

y = "Words preceded by a negation")

Figure 9.9: Words that contributed the most to sentiment when they followed a ‘negating’ word

It looks like the largest sources of misidentifying a word as positive come from “don’t want/like/care”, and the largest source of incorrectly classified negative sentiment is “no problem”.

9.4 Summary

In this analysis of Usenet messages, we’ve incorporated almost every method for tidy text mining described in this book, ranging from tf-idf to topic modeling and from sentiment analysis to n-gram tokenization. Throughout the chapter, and indeed through all of our case studies, we’ve been able to rely on a small list of common tools for exploration and visualization. We hope that these examples show how much all tidy text analyses have in common with each other, and indeed with all tidy data analyses.